From New Atheism to millennial socialism

My first post on Substack, long since deleted, was an attempt to trace the influence of the New Atheists on the Dirtbag Left. I deleted it for a few reasons: (1) I have very little direct experience with the New Atheists and didn’t actually want to research them; (2) Scott Alexander, I later learned, already wrote a similar piece with broader and more persuasive claims about New Atheism’s effects on political culture; and (3) I realized that this was a really stupid thing to write about and I should just keep to literature. But basically, my argument in that piece was that the Dirtbag Left—or the Online Left, I should say more generally—both mirrored the New Atheist critique and turned it against itself.

For instance, New Atheists castigated Christians for purporting to believe in love, charity, and peace, while in actuality turning away from homeless people, supporting policies that harmed vulnerable groups, and purchasing private jets for their pastors. They carved out an anti-establishment third space between Christian neocons ready to carpet bomb the Middle East and liberal multiculturalists unable to criticize Islam. It also created a style of quick-witted internet takedowns that inspired both left-wing Twitter trolls and right-wing “destroying feminists with facts and logic” YouTube videos.

Fast forward a few years. For socialists, being a “lib” would carry the same stigma of stupidity, hypocrisy, and moral bankruptcy—despite publicly preening their virtues—that being a Christian implied for atheists during the aughts. Moreover, being a socialist/leftist would imply the same virtues that atheists formerly claimed for themselves: rationality, global concern, and moral clarity. Liberals are just against anyone having fun, you sometimes hear people on the Left say when Democrats consider things like vape bans. A couple decades ago, that sentence would have started with “Christians.”

I won’t continue with this pseudo-historiography, but I would note that the would-become socialists broke with the New Atheists after the latter came around on the idea of US liberal interventionism in the Middle East. And I say pseudo-historiography, because I have no actual evidence for any of this beyond rhetorical posturing and being terminally online. My hunch is that the Online Left broke from the New Atheists by seeing that atheism, melded into a political project, found ready justifications for US supremacy, endless wars in the Middle East, and anti-Arab racism. Season one of Chapo Trap House, for instance, should be understood in this context.

Anyway, I gave up on this line of inquiry for a while and deleted the post, but lately I’ve been drawn to thinking more about the relationships among religion, politics, and American culture. It started during a few months back when, in need of background noise, I started listening to The Trillbilly Worker’s Party again—a communist podcast out of Appalachia that frequently touches on the hosts’ Evangelical upbringings and current agnosticism/atheism. In one episode, a host admits that his belief in communism is essentially a material rendering of his former belief in heaven. This is an old point: modernity took the salvific claims of religion (while retaining religious biases) and applied them to the earthly realm of politics. Liberalism sees perfectibility through amelioration, like Christians monitoring their sins and ceasing them to become more like the image of Christ (while admitting that perfection is imposible). Communism overturns the established order through a revolution to bring about heaven on earth, like a messiah coming for the Jewish people. Listening to the Trillbilly host enact a brief comedic skit where some rich men screamed while being tortured for their criminal amounts of wealth, I wondered whether he wasn’t revealing that, though he may have left religion, his politics were deeply influenced by nostalgia for both heaven and hell.

This took me back to my earlier post. I think it’s easy to look at charts showing the precipitous decline in church attendance and religious belief among younger generations and see the incipient death of religion in America. Hipster Catholicism doesn’t seem likely to reverse these trends, and Christian nationalism seems more like a Christian-branded political movement than a spiritual reawakening. And yet I think religious nostalgia is a cultural force worth watching. One could argue that socialism took off on Twitter because it appealed to millennials who grew up in the church, left it, and continued to desire religious optimism.

I think it’s mistaken to take the ambient interest in religion among the intelligentsia and culture industries in the years since 2020 and say that religion is emerging from the grave. Rather, it’s merely decoupling from political projects. With politics stagnant on a practical level, it can no longer bear spiritual aspirations, and people need some way to grapple with their hopes, fears, ideals, and powerlessness. Religion provides a form for those anxieties.

The God pivot

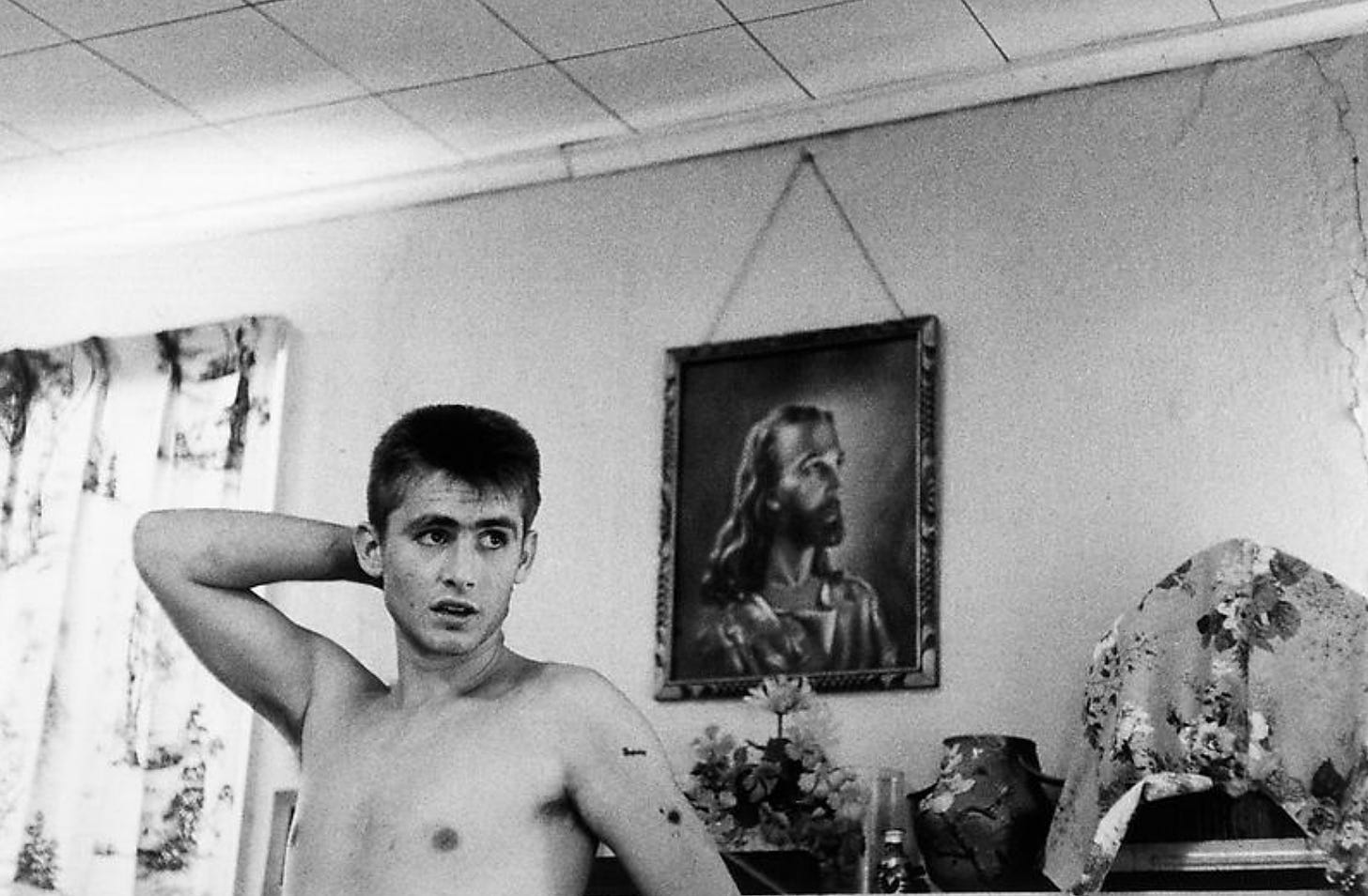

The simmering interest in God in the zeitgeist has perplexed me for a while. In writing the final installment of my Gym Theory series, I touched on the omnipresence of Christian symbols or expressed Christian beliefs in gym culture. I landed on the claim that Christian signifiers fit within this ideology of strength—in this case, by displaying one’s spiritual strength, otherwise invisible. Unlike “spiritual but not religious” agnosticism, Christianity—as a specific form for spiritual feeling—implies a kind of discipline in itself. Religion offers a “mindset” by demanding adherence to a specific set of values. Claiming a religious identity becomes an easy shorthand for communicating in short-form media that you live by a certain code of virtues. You’re not a boy, you’re a man.

Or perhaps it’s just a convenient way of masking one’s aloneness as something sacred and noble.

I’m taking the point further than I did in my Gym Theory post. My earlier decision to demur was because I couldn’t convince myself of a nuanced explanation, even though I also couldn’t believe that their Christianity had nothing performative to it.

So it piqued my interest a month ago when, via Spotify recommendations, I saw an episode of the Conspirituality podcast on the “God pivot” recently taken by Russell Brand, Joe Rogan, and Andrew Huberman—three popular online figures all existing in the same general, right-leaning, health and fitness media ecosystem. Individually, they affirmed their belief in God—even specifically a Christian God in Brand’s and Rogan’s cases—despite earlier or implied atheism. The Conspirituality hosts played these various confessions and threw out a few possibilities for why these figures may have decided to publicly embrace God. Brand’s case, given the allegations of sexual misconduct against him, seemed straightforward enough: I believe in Christian forgiveness so you have to forgive me. Like Jesus, I’ve been martyred by my enemies, etc. The hosts’ explanations for Huberman and Rogan were rather cynical. The two could be trying to get out in front of sexual misconduct allegations, à la Brand, or they could be hedging their bets on the fomenting Christian nationalist movement by appealing to the Christians in their right-leaning audience.

Both possibilities struck me as overly cynical. With Huberman’s case, the answer seemed obvious. Though I only knew vaguely of him through the online gym community (and even joked about him in January), I dismissed Huberman as a weirdo optimizer type who appeals to young straight guys who are sexually attracted to him but tell themselves that they’re actually mimetically interested in him. I just want to be like him and become a better version of myself. No, you want him to shove your face into a pillow while he’s working your prostate with two fingers, just be honest lol.

Sidebar: The secret teachings of Freud

I imagine one day we’ll discover a lost manuscript of Freud with all his secret teachings, like the Dead Sea Scrolls. The key revelation will be that the Oedipus complex clinically exists but takes an inverted form, i.e., all men unconsciously desire to kill their moms and fuck their dads. This may not be an enduring desire, but empirical evidence will show that it inevitably emerges at a certain point, usually during one’s early-to-mid twenties. Put succinctly, all young men, regardless of their sexual identity, want to be fucked by a daddy.

The dividing line, and really the psychologically revealing point, is how they want to be fucked. Some clearly want daddy to slap them around and make them his bitch. Others want him to be slow and tender. Others still just want to be done with it, but know it’s their duty to their daddy. Though rare, there are some guys whose primal need is to top their daddy—just completely rail him out until he’s a slobbering mess/cock slut. You’ve really gotta watch out for that type. Stay woke.

A brief moment of self-awareness

Sometimes I like to look over my work and think, This is what I’m depriving academia of.

The God pivot (cont.)

As I was saying, though the Conspirituality hosts seemed genuinely baffled by Huberman’s newfound religious feelings—they puzzled over why he was reading the Bible to quell his spiritual longings instead of digging into new areas of biology scholarship (🤦♂️)—I felt his God pivot was immensely understandable and even had precedent. Before him, Tim Ferriss was the self-optimizer guru, and he published books about optimizing your work life, fitness program, and sex practices (not kidding—he includes diagrams for optimizing clit stimulation). But my understanding of Ferriss’s trajectory is that he became so depressed that he reinvented himself as a shroom guy and now extols the wonders of psychedelics.

The optimizer behaviors that Huberman advocated for offered a greater veneer of scientism (though maybe not actual science) than Ferriss’s did but seemed like an equally soulless way to live: life reduced to minutes and milligrams. To some, this kind of regimentation has the quality of a secular prosperity gospel to it, but I think that after you live it for so long, you inevitably become disillusioned and ask yourself broader philosophical questions about what you’re doing and why. Even if you have a longer and healthier life as a result of your dogged health-freakism, you’re just spending it swallowing vitamins all day, repeating stoic mantras, and worrying about your dopamine levels, lest you enjoy anything. Belief in eternal life might just be a good longevity protocol, but I felt it was understandable why someone like Huberman would inevitably be drawn to a religious worldview to address the hollowness at the core of self-discipline.

Daddy Huberman

Literally three days after I had these thoughts about him, New York magazine ran an exposé of Huberman, alleging his serial cheating and shitty behavior toward women. To some, it was damning of Huberman; to others, it was damning of the media. I was mainly annoyed that my hypothesis was wrong: Huberman’s God pivot was probably a preemptive PR move against this exposé. I wasn’t cynical for one second and was swiftly punished—truly evidence of God. It seemed like the sort of scandal that would pass in a couple days, and it did. But I watched it intensely because I was now intrigued by the question, What’s up with parasocial dads? Because clearly, the sense of “betrayal” some felt stemmed from the twin filial horrors of their dad having actual sex and failing to live up to the idealized image they held of him.

When I look over the span of my online life, I would say I’ve been prone to developing parasocial interest in people who are in my relative age group. The template of our relationship is friendship. But there seems to be a type of young man—really, extending into his thirties—who has a preference for parasocial father figures, such as Jordan Peterson or Huberman. I don’t instinctively see the appeal. I’ve always been rather strong-willed and didn’t put much stock into “role models,” which holds a hint of pop psychology to it or, at the very least, culture of poverty bullshit. I also felt, growing up, that the cultural message was that parents were fundamentally lame. (Say what you want about how punk pop diluted the message of authentic punk, but punk pop was unambiguously anti-parent.) Even now, I have a decent relationship with my dad, but I wouldn’t turn to him for life advice or to disclose parts of my personal life—a fact I think we’re both grateful for. I would die from embarrassment if he tried to “talk to me as a man.” Nah, sorry, I don’t care if you’re my dad; you’ve just gotta take some of that shit to the grave.

Might be worth disclosing that I grew up in the ever-stoic Midwest.

In different guises, I posed the parasocial dad question around the internet, because there’s really very little that you can extrapolate from your own family. The general response was that there are a lot of shitty or emotionally absent dads out there, and young guys feel so unmoored that they need someone to give them basic life guidance and a reason for it, whether it be mythic (Peterson) or scientific (Huberman). Such figures marry everyday behaviors with aspiration. Unlike parasocial friends, who might be aspirationally funny or clever, parasocial dads are aspirationally smart, virtuous, or strong. People who defend Peterson and Huberman say that they helped them get their lives together. This term is dirty and millennial, but these figures are essentially “adulting” influencers for zoomer boys—just slightly less blergh-y in their presentation. For millennials, adulting was semi-ironic and quickly became cringe, but now, it has become so normal that it doesn’t even register as what it is.

Despite my “this is all just sublimated, though very hot, homosexuality” jibes, I do understand the deep, almost spiritual appeal of having an older man notice and care for you, especially when you’re at the age when your parental bonds weaken, you feel very alone in the world, and you honestly just suck at taking care of yourself. Boys are raised rather carelessly and with the expectation that they’ll figure it all out on their own or simply find a woman to finish raising them. The fantasy of these specific parasocial dads embodied wasn’t a vision of lavish wealth, hot babes, and power, but a rather homely fantasy of wanting to be a decent person who has his shit together and has earned his and others’ respect through his character and actions—which, of course, neither Huberman nor Peterson has lived up to. But I understand the appeal. It’s about living an honest life.

The parental bond

For a while, I was dismissive of these parasocial parent relationships on different grounds. Reading the comments left on videos by “gentle parenting” influencers—this trendy form of non-parenting inspired by therapy—I assumed that zoomers gravitated toward such figures out of a narcissistic sense of their “thwarted” potential: I would have been a good person who liked herself if my parents didn’t traumatize me by taking away my iPad, etc. So I didn’t think much of it. After all, it’s fairly common to examine your parents critically after you move out, and these videos offered viewers a fantasy of an alternative childhood and self formation.

But I’m wondering if the shift from parasocial friends to parasocial parents doesn’t register a deeper loneliness in young people. I’m reminded of Sam Kriss’s essay on incest porn. Kriss writes:

Pornographers invent family stories for the same reason screenwriters do: it’s a way of establishing a relation between two characters without having to deal with any kind of actual sexual desire. A role, set in advance—sister, daughter—instead of the sheer implausibility of another living person. Not fantasy, but rather, familiarity: the only thing remaining once fantasy has gone.

Have the prospects of friendship and romantic love faded so much that the perdurable lines of family are what we want to fall back on? Something more unconditional?

Maybe it isn’t so grim, idk. Despite Knowing Better, I slip into the cultural tendency to equate someone’s character with the podcasts they listen to. We used to do the same with music (e.g., Male Manipulator Music), and now people defend their podcast habits the same way. The 10 percent of people on /r/redscarepod who actually listen to the podcast always recite the same litany: I listen to it but just for the vibe; I don’t endorse all their takes; I just like hearing dumb girls talk ahaha. Weird behavior, but I also removed a reference to an old Felix Biederman tweet above so you wouldn’t think I’m a Chapotard instead of someone with a totally unique and cool worldview, sense of humor, and dick shape.

There does seem to be something special about podcasts, though, that encourages us to see them as summations of a listener’s character and viewpoint. Perhaps just the suspicion that people won’t say what they believe—and may not even be able to articulate it anymore—but betray their beliefs and character by what they’re willing to listen to. Maybe, in a post-religious age, we should dismiss friends and parents as second-rate frameworks for thinking about parasociality and instead think of podcast hosts as priests, which is, I grant, an embarrassing overstatement and yet what people truly seem to fear they are. At stake in listening is the tantalizing possibility of genuine conversion—a riff that goes on so long that it turns into sincere belief.

Listening to a podcast is the closest some of you heathens get to hearing a sermon, I can tell you that much.

Spring recs

Been a while since I did this.

Vintage The Onion: Obviously, The Onion’s quality is hit or miss, with more misses than hits in recent years. But if you’re looking for an altogether enjoyable way to pass an evening, check out The Onion’s season 1 playlists. (This video was my favorite in high school.) Their true-crime podcast had some good moments too.

CVS coupons: Because of inflation and everything else, coupons in general seem basically worthless (50¢ off?? Go fuck yourself). But if you use your CVS card and sign up for mailers, you get like two 40% off coupons for any item under $100 every month. I’m saving so much money on protein powder that I’m willing to shill for CVS in my ultra-subversive, far-far-left newsletter. You need to get on this shit.

Horny posting on Substack: Dating apps don’t work anymore. The problem is downriver from the algorithm or business model: everyone’s become too cynical for them to work. You know what hasn’t been tried? Horny posting on Substack. Statistically, at least one of you is a decent-looking single man. It’s cool if you’re straight; I’m straight too. Tops only.