Couch to 5K to StrongLifts 5x5

In the early 2010s, everyone ran. Distance running fit the moment. Gentrification made city streets safer, and iPods and smartphones insulated runners from the cityscape. Couch-to-5K, a viral training program, democratized fitness knowledge and was basically foolproof. To use another buzzword from the moment, the program gamified exercise (sometimes literally), turning it into a series of small goals and larger ones that you worked to achieve. The races themselves, which became elaborate and included obstacles, often looked like games: paint splashes, glow-in-the-dark shirts, and zombie chases. Races rewarded runners' efforts with a medal, which they could post on social media, and a clear sense of accomplishment. It was the perfect exercise for the hoop-jumpers everyone was supposed to act like.

Why has lifting taken the place of running as the exercise? Was it simply the triumph of the image on the social media platforms that emerged? Did we finally learn that, no, runner’s abs aren’t real and long-distance running certainly won’t grow your pecs?

The appeal of lifting is murky when you think about it. It encourages discipline without achievement. You can gain a sense of progress, but you don’t have a finish line; even men ballooned up on steroids continue to fret about pumps and muscle ratios. Running was often a solitary exercise, but lifting, though it usually occurs within a social context, is often lonelier, performed in a sea of monads. The gym is a unique blend of public and private space. Perhaps the retreat from jogging in the streets betrays a growing suspicion of the public and the entrenchment of private space in public life, even just the bubble around your head.

As I said in the preface to this series, my contention is that lifting has gained in popularity because its message of strength meets the psychic needs of a moment when it feels like society is in decline. To say that lifting is about strength appears tautological, but physical strength is secondary to the internal strength that’s really at issue: the strength to overcome mental struggles, romantic failures, loneliness, educational purposelessness, career uncertainty, institutional delegitimization, and so on. Of course, looking good is a motivation too. What’s the point of getting your shit together if you don’t become hotter by the end of it? Yeah, there’s a certain narcissism at play, but let’s hold off on that part. There’s something else here.

Messages from GymTok

It all went downhill after “how to get a six pack in 10 minutes”

boys this is your sign to take a break from drinking, start working out, and get a buzz cut

Aesthetics>>school

Your competition is not others. It’s your laziness, the junk food you eat, the knowledge you ignore, your lack of discipline, and the negative energy you tolerate. Compete against that.

Me completely destroying my legs with 135 pounds in the gym… while the girl of my dreams is most likely getting completely destroyed by a 135 pound drug/nicotine addict…

Coming of age

You often hear the line that Nobody Wants To Grow Up Anymore. It’s understandable why you hear it everywhere: in making this argument, the speaker positions themselves as The Adult In The Room, the gatekeeper of lost knowledge and moral superiority. It might also be true to a large degree. But perhaps what it means to come of age hasn’t been abolished, but transformed.

Let’s begin there.

This is what sociologist Jennifer Silva found in her book investigating how working-class young people in deindustrialized US cities understood their own coming-of-age processes. Previously, coming of age had material signifiers—higher education, marriage, children, home ownership, steady employment—that neoliberal economic restructuring made either unattainable or much harder to secure. But Silva’s findings reject the idea that people consequently see themselves as stuck in permanent adolescence (even if critics maintain otherwise). She argues that coming-of-age narratives are “purchased not with traditional currencies such as work or marriage but instead through the ability to organize… difficult emotions into a narrative of self-transformation,” often wrapped in therapeutic frameworks. One stakes a claim to dignity by conquering one’s inner-demons (e.g., mental illness, addiction, sexual expectations, religious guilt).

With echoes of Lasch, Silva is skeptical of these new coming-of-age narratives. She describes their darker side, which leads “young adults to draw harsh boundaries against their families, to become suspended in the narratives of suffering they believed would bring them promise, and to construe the self as their greatest risk in life.” The “imperative to heal oneself” also draws “boundaries against those who do not have the will to be healthy, happy, and strong.” We see both these attempts at self-transformation and their downsides so often that these observations hardly need further explication, though I’ll return to the latter in the next part. But the important point to draw is that coming of age has been reconfigured from a negotiation between the self and the community to a negotiation that occurs within oneself, between the past and the present or the ego and the ego-ideal.

In that sense, the gym has a narrative function as a proving ground for coming of age, where one fights against family, ex-lovers, mental illness, obesity, addiction, etc., to establish a new, confident self that one can respect and expect others to respect too. The notion of the “winter training arc,” for instance, which was nabbed from shounen anime, makes this narrative function explicit: lifting serves as the turning point between two moments in the story, one that leaves you, the main character, changed for the better—stronger and self-possessed, able to rise up to the challenges that once could have defeated you.

This process is psychological perhaps more than physical, and it’s no surprise that lifting often goes hand-in-hand with stoicism as philosophical practice. Stoicism, at least in its popular instantiation, is a male-coded cognitive behavioral therapy in which you act as The Adult In The Room in your own psyche, monitoring and reframing your thoughts and defusing powerful emotions, associated with immaturity. The ability to mindfully disengage from entrenched and reflexive behaviors and take a more “rational” approach demonstrates one’s adulthood. The goal is for your mind to become like the metal you’re lifting.

In short, the gym offers the fantasy of a total transformation of the self, internal and external. Sure, it plays into this neoliberal notion that one cannot change the world, only oneself. But to appease the Marxists in the audience, I’d just say that for people who feel broken and lost, the agency to change oneself is also a powerful repudiation of a system that wants to beat them down. Broken people don’t riot; they rot.

Might is right

Or broken people learn to lift weights. The heaviest weights you lift are your feels, goes a common meme.

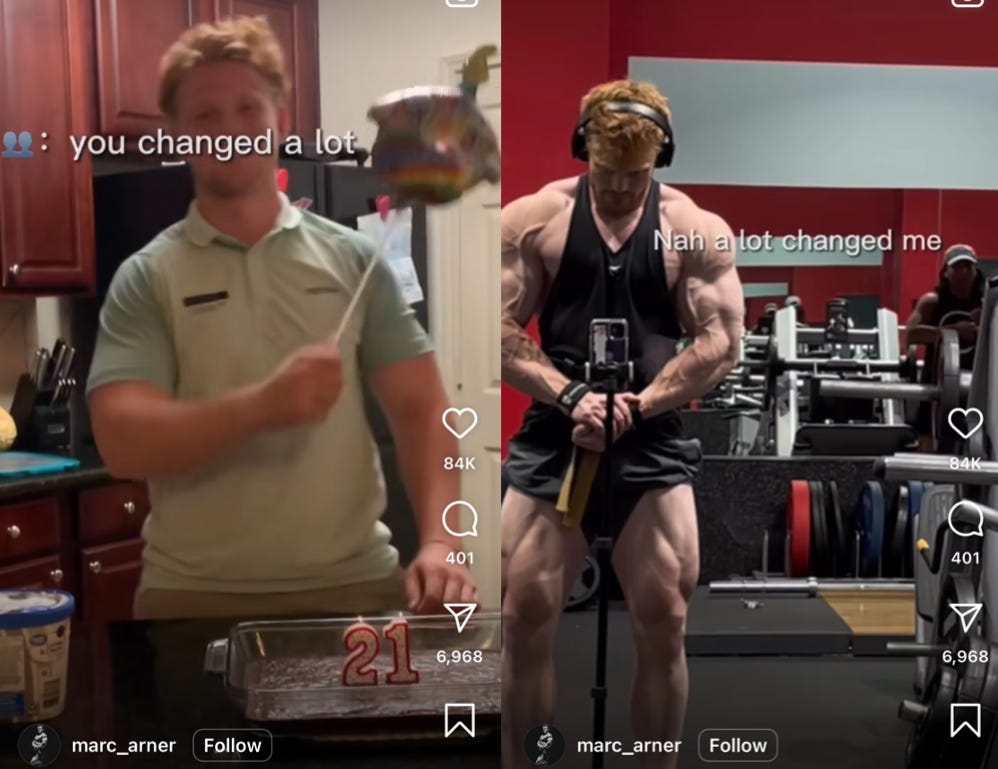

The narrative structure of the progress pic—before/after—is the same as the coming-of-age narrative and also the trauma narrative: before the life-changing event and after it. Silva’s revised structure for the coming-of-age narrative could be considered a form of what Parul Sehgal calls the trauma plot. Sehgal argues that most contemporary narratives (whether in fiction, film, TV, or life) feature characters defined by a traumatic past of some kind; the forward momentum of the plot is, paradoxically, the revelation of the past trauma and its confrontation. Told through this lens, coming of age isn’t about becoming the sort of person who can face his future but the sort of person who can face his past.

Sehgal only takes her analysis to midfield. Pain may give you a story; it doesn’t give you the right to tell it, especially when you assume that nobody will care. For men, the therapeutic truism that “it takes strength to be vulnerable” has a literal dimension. It’s easier to be vulnerable when you aren’t weak. It might be masculinist bullshit, but there’s a sense of self-ownership that comes from building muscles. It isn’t just ownership of the body. It’s a right to narrate one’s life. Expressing struggles and vulnerabilities is not a sign of strength so much as a privilege of the strong. And with it also comes the capacity to be funnier, gentler, kinder—a sense that what you call your personality is a defense mechanism against your own weaknesses or perhaps a sense that, if you’re strong, others will forgive you for having dimensions to your character.

Nymphet Alumni suggests that this is why gym influencers eventually open up about their Mental Struggles in an almost big-brotherly way. It isn’t just that influencers are desperate for content and will turn inward to monetize to supplement the monetization of their bodies. But there’s a sense that you don’t earn the right to your story—to your self—until you’ve conquered it physically. That’s how you become a man to other men.

Persons of no particular gender

To be honest, some of the masculinist bullshit is part of the appeal of the gym.

“I was a young, strong, stingy person of no particular gender,” the poet Anne Carson writes in a diary entry. It’s that last phrase that has interested me in the years since I first read it. It put a fine point on what I had experienced or, rather, hadn’t experienced growing up: a strong sense of gender. A feminist might say that I was oblivious to my gender as a result of male privilege, but I wouldn’t say that I was oblivious—just indifferent. Maleness seemed easier than any alternative, and yet this tendency toward ease also warded me off from stereotypical masculinity. An article I once read in a masculinity studies journal argued that, for boys, a kind of ersatz femininity is their default gender, whereas masculinity must be proven continuously and, by extension, can be disproven in a single instance. Which seems right—I just didn’t feel like proving anything.

Even well into my twenties, I remained indifferent to my gender. As they became fashionable, I mulled over labels like nonbinary and agender for maybe half an afternoon before I decided that I really didn’t care enough to make a claim to a term (same with my sexuality, though I officially “came out”—a move that, in retrospect, strikes me as mildly surprising). But ever since the pandemic, I have felt a deeper attachment to masculinity for reasons I can’t entirely explain. Perhaps a greater responsibility over my life or nagging paternal instincts. Or it’s because I now almost universally pass as straight or because I got into weightlifting. Or maybe the trope of Lonely White Men had become so available at that point that I had a cultural narrative and identity to insert myself into.

Regardless, after years of waffling over meanings, I’d say that, yes, I’ve Become A Man, which has been a strange process because I seemingly circumvented boyhood. What does manhood mean for someone who hasn’t been a boy?

Male-to-male transgenderism

This question isn’t always formulated so bluntly by the people who talk about it online—most of whom presumably grew up, like most nerds, with a weak gender identity but have, for reasons ranging from personal, aesthetic, sexual, to political, come to pursue a stronger sense of their maleness, perhaps out of step with their actual age, through lifting.

I’ve said before that the circumstances of the culture war make it instructive to identify and reflect on a person’s Jungian shadow. In the case of online lifting communities, the obvious shadow is fat people; the hatred that fat people receive is very clearly just a form of physical and moral self-disavowal. But the other shadow you’ll notice is trans people. If you compare /fit/ and /lgbt/ (dubbed /tttt/ for the prevalence of trans-related topics), you’ll see the similarities immediately:

Hormone therapy: steroids, SARMs, testosterone-enhancing supplements (e.g., ashwagandha and tongkat ali)

Top surgery: corrective surgeries for gynecomastia

Passing: getting out of DYEL [Do You Even Lift] mode

Gender validation: getting mired

Gender dysphoria: body dysmorphia

Transvestigation: natty or juiced

Personal identification with anime characters: Goku, Luffy, Naruto, Midoriya, Gojo, etc. (only half-kidding on this point)

Muscles do not express a gender so much as they produce it. Or perhaps I should say that they produce confirmation of it. (Consider the cultural link in the US between male skinniness and presumed gayness.) But if you become aware that gender is, at least to a degree, performative, then you have to admit a harsh conclusion: You Will Never Be A Man. Transphobia is a scapegoating of this psychological fear. All you can do is increase your legibility as a man through physique, hormones, surgeries, jawmaxxing, mindsets, body count, etc. But beneath these attempts is the obliterating sense that in trying to become a man, you only end up trans for your own gender.

Touch steel.

My earlier story about growing up without a gender might sound like a rip-off of a passage from Bronze Age Mindset. As an aside, I should say that I wanted to pass over the Bronze Age Pervert (BAP). He is passé, and his only contribution, really, was to rebrand right-wing anons as secretly very hot, despite all evidence. But neglecting him would feel like an omission, especially given the next installment in this series. So bear with me.

The second part of Bronze Age Mindset is essentially a critique of the coming-of-age narrative. It begins with the illustration of a dog whose predator instincts remain but express themselves dully in domesticated environments. The dog is, in BAP’s analysis, “[p]laying at becoming itself, but reduced to a doll and useless acting.” He draws this point into an analogy with young boys on a playground, observed through the lens of a proto-gay boy who perceives the other boys’ competition and horseplay not as true masculinity but as a farce of it, unfurling in an enclosed simulation (rather than as real preparation for war and conquest). The proto-gay boy eventually eroticizes the circumstances he is born to rebel against—whatever, whatever. The interesting point, I think, is that the coming-of-age narrative can usually be distilled to “becoming what you already are,” but BAP argues that it has become “playing at what you should be.” Which is to say that boys grow up not to become men but drag kings.

There’s some irony, then, to the suggestion, in BAP’s work and in the thought of his acolytes, that one should “touch steel.” Yukio Mishima’s Sun and Steel may not resolve homosexuality, alas, but it encourages direct contact with the material world as a means of self-actualization and growth; I’ve heard someone refer to Mishima as a self-help guide to curing yourself of internet autism (which might be as “curable” as homosexuality). The irony, of course, is that the gym has long been held as an enclosed space of simulated masculinity; even women’s erotica draws the difference between the muscles of urban gym yuppies and the muscles of sexy country farmhands. But the fantasy is, as always, more illuminating than the counterargument: the gym is a form of pursuing the truth about yourself and reality beyond the received simulation.

Which—forgive me if this is a stretch—is a very interesting idea to push at college-aged men. After all, isn’t that the supposed goal of the university? The gym has become the new school. One doesn’t need knowledge or education; only strength and discipline have the capability of revealing reality. Hence BAP’s taunt:

The left realizes they look weak and lame—because they are. They know they have nothing to offer youth but submission and lectures. They know they’re unsexy and staid. If indeed young leftist men will start lifting and worshipping beauty, they will be forced to leave the left.

Though the reasoning has no logic, the overall critique of the Left—at least the Online Left, to whom BAP is throwing this gauntlet—isn’t entirely wrong. It also isn’t entirely an incorrect statement to level against the Online Right either, which has its own deep fetishization of victimhood, but cites “modernity” instead of capitalism. If I risk making the horseshoe fallacy, it’s because online subcultures tend to function the same way and reward the same things: misery, injury, and dark humor. Perhaps the most accurate statement would be that if young people start lifting and worshiping beauty, they will be forced to leave the internet.

And that’s the dream, isn’t it—coming of age by going offline?

#HotBoysForBernie

Maybe we’re supposed to keep this a secret, but the Bernie 2020 men’s shirts fit very snugly in the chest, allowing even sloppy soyboys the fantasy of pecs lol

It would be unfair to present critiques this early in the series. However. I feel all this theorizing somewhat begs the question. If it's about discipline and transformation, why the focus on lifting (which is fundamentally about consumption) and not on ascetic self-denial, like the sadhus of India? The BAP quote is indeed telling, because it reveals the unspoken assumption at the heart of this culture. It's not about improving yourself, but about making yourself more attractive—more fuckable, to be vulgar and honest. Mishima is the perfect example. His bodybuilding resulted not from his philosophy of life expressed in Sun and Steel; that was a post hoc rationalization which failed to disguise much of anything. He was a gay man who admired athletic bodies and loathed his own body for being skinny and weak. In order to achieve the death (apocalyptic orgasm) he desired, he had to reshape his body into a form that could match his fantasies. None of these gymcels are going to commit hara-kiri at West Point, though, because they're just microdosing the insanity which Mishima overdosed on.